This is not for the feint hearted. No research project is, really. I’ve never come across a scholar who hasn’t got grit, determination and sheer perseverance. Then again, I am old-fashioned (in the nicest sense) and I place Umberto Eco’s How to Write a Thesis (1985) on such a high pedestal (for many reasons; some not relevant outside the context of teaching students the principles of ‘good research’).

Approximately hundred photographs started the process…And then some of the dancers in these photographs (or their daughters) began to send me theirs. The material snow-balled. It’s taken me two years to work out the material (although I admit to having breaks, including birthing a baby boy, organising conferences in New York and Sydney, and brainstorming a new anthology on contemporary ballet).

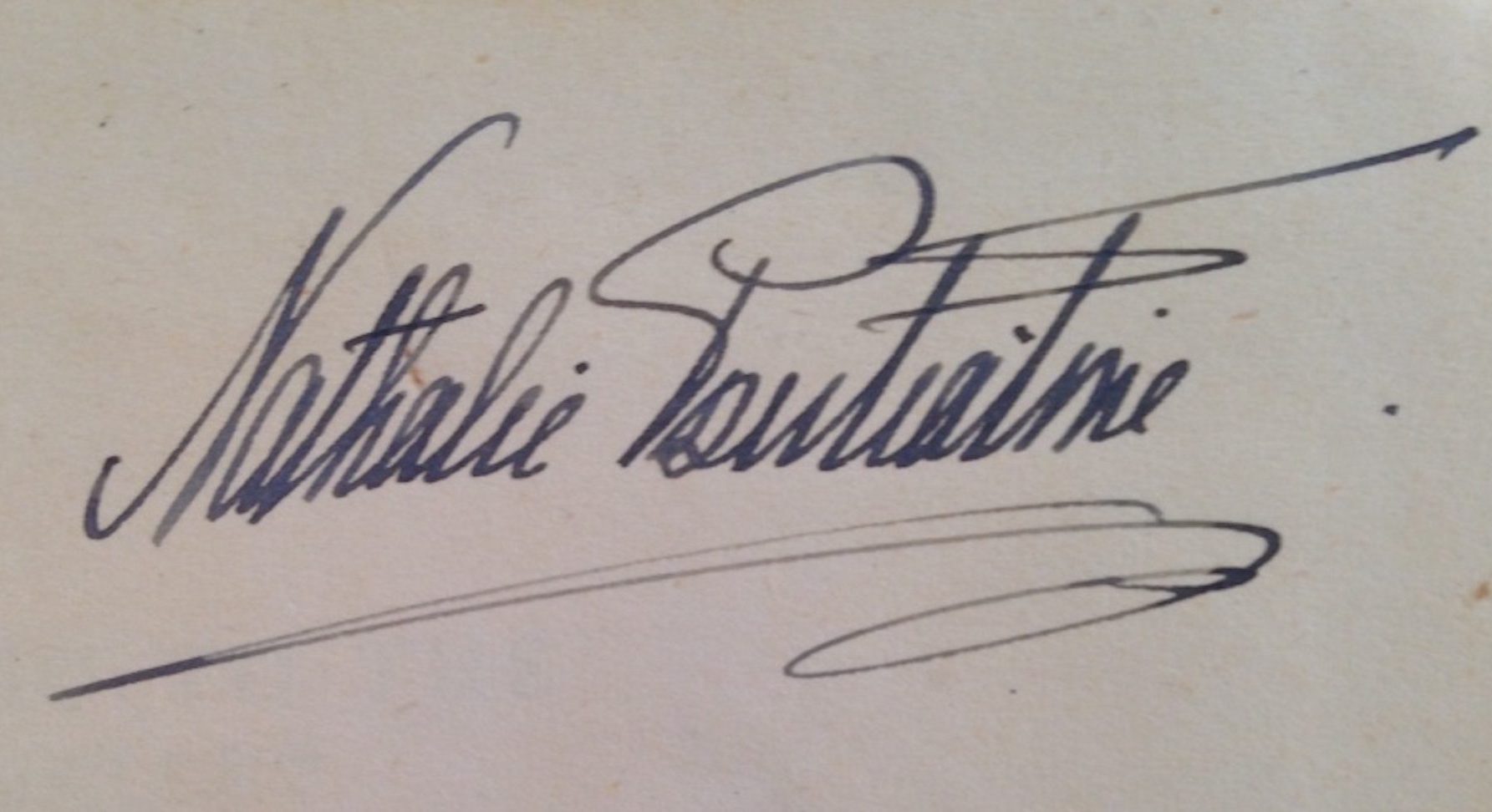

Back in 2014, Tanya Bayona, custodian of the Poutiatine legacy, granted me access to Poutiatine’s photographs (as well as other memorabilia). A year later I went back to Malta. During the warm days June/July 2015, I waded through, photographing all these photographs. Identifying, cross-checking, re-checking, finding errors in the matching up of photos to programmes. The piecing together of the puzzle has kept me busy for a few years now. But when digital copies of the last programme (Manoel Theatre, 1961) came through via email, the majority of the visual narrative came together.

Now the writing up stage begins…

In the meantime, I’m flitting between Henry Frendo’s Europe and Empire (2012), thinking about how ballet can/can’t decolonialise a colonial past and culture, and also make a quick phonecall to one of Poutiatine’s dancers from the 1949 concert. It’s a little crazy…but in the manner of how the book project all started, its the gathering of the data that isn’t for the feint hearted!